By Patricia Hart

In one Maryland town, November 5, 2013 was no ordinary Election Day: it marked the beginning of a historic expansion of suffrage rights to 16- and 17-year-olds. On October 30th - the start of the city's early voting period - Takoma Park became the first city in the United States to open its polls in a general election to residents after they turn 16.

In one Maryland town, November 5, 2013 was no ordinary Election Day: it marked the beginning of a historic expansion of suffrage rights to 16- and 17-year-olds. On October 30th - the start of the city's early voting period - Takoma Park became the first city in the United States to open its polls in a general election to residents after they turn 16.

They Showed Up and Showed Off

Voter turnout in Takoma Park's municipal election was notably low, a likely result of no contested races or referendums. Nevertheless, 16- and 17-year-old residents still came out to vote.

Turnout rates were significantly higher among 16- and 17-year-olds than that of the overall population. The official turnout number of the age group is 59, approximately 17% of eligible voters under 18 - which is double the 8.5% turnout rate of eligible voters 18 and up. The difference in turnout is stark when you consider registration rolls. Close to 42% of registered people under 18 cast ballots, which is four times the rate of registered residents 18 and older who voted.

Residents in their 20s had the lowest rates of participation. In both the 2009 and 2011 elections, fewer than 30 people voted who were between the ages of 18 and 25, which is between 1% and 2% of eligible voters in that age group. Only 25 people between 18 and 25 voted in the city’s election this year. In the 2011 city election, the turnout number was even worse; only 14 people in that age range cast ballots. Local supporters of the lowered voting age believe introducing young people to voting before they turn 18 will increase turnout among people in their 20s because 16- and 17-year-old voters will continue to vote once they turn 18.

During early voting on Friday, teenager Alanna Natanson became the first person in the United States under 18 to cast a ballot in a general election. While originally nervous that the process would be a difficult undertaking, Natanson said voting was easy in Takoma Park.

Voter turnout in Takoma Park's municipal election was notably low, a likely result of no contested races or referendums. Nevertheless, 16- and 17-year-old residents still came out to vote.

Turnout rates were significantly higher among 16- and 17-year-olds than that of the overall population. The official turnout number of the age group is 59, approximately 17% of eligible voters under 18 - which is double the 8.5% turnout rate of eligible voters 18 and up. The difference in turnout is stark when you consider registration rolls. Close to 42% of registered people under 18 cast ballots, which is four times the rate of registered residents 18 and older who voted.

Residents in their 20s had the lowest rates of participation. In both the 2009 and 2011 elections, fewer than 30 people voted who were between the ages of 18 and 25, which is between 1% and 2% of eligible voters in that age group. Only 25 people between 18 and 25 voted in the city’s election this year. In the 2011 city election, the turnout number was even worse; only 14 people in that age range cast ballots. Local supporters of the lowered voting age believe introducing young people to voting before they turn 18 will increase turnout among people in their 20s because 16- and 17-year-old voters will continue to vote once they turn 18.

During early voting on Friday, teenager Alanna Natanson became the first person in the United States under 18 to cast a ballot in a general election. While originally nervous that the process would be a difficult undertaking, Natanson said voting was easy in Takoma Park.

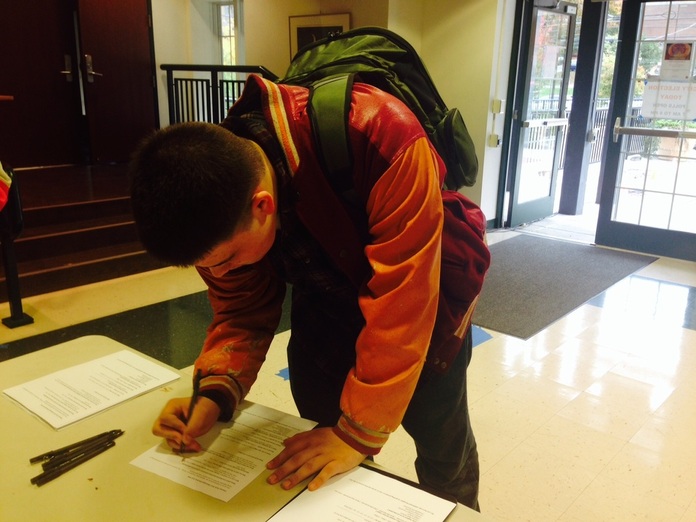

FairVote staffer Patricia Hart speaks with Nick Byron, 17-year-old voter,

FairVote staffer Patricia Hart speaks with Nick Byron, 17-year-old voter, about casting his first ballot.

FairVote also spoke with 17-year-old Nick Byron at the polls on Election Day. Byron had advocated 16-year-old voting when the charter amendment came before the Takoma Park City Council last spring, and continues to be an outspoken supporter of the policy. “16- and 17-year-olds should be able to vote because they are rooted in their communities. 18-year-olds are going to college, while we are living with our parents, taking civics classes, and thinking about the city,” Byron explained.

Right to Vote Resolutions Spark New and Innovative Policies

The seeds of this change were planted last winter, when Councilmember Tim Male began crafting a Right to Vote Resolution -- in partnership with FairVote’s Promote Our Vote project. The resolution called for a constitutional right to vote, established a voting task force, and took stances on a variety of voting rights issues. By sparking city-wide dialogue about what it means to vote and be civically engaged, the resolution catalyzed efforts to lower the voting age. As Male explained to FairVote, the Right to Vote Resolution created an environment where the idea of a lower voting age – one that several of his colleagues initially treated with skepticism – was taken seriously.

By spring, the city was engaged in a lengthy debate over the charter amendment that, among other changes, lowered the voting age in city elections. Central to this discussion was the city’s youth turnout crisis. A mere 14 voters between the ages of 18 and 25 showed up to cast a ballot in Takoma Park’s last contested mayoral race. That dismal number means that more than 99% of Takoma Park residents between the ages of 18 and 25 did not vote. While the city agreed that it had to improve youth turnout, lowering the voting age seemed so revolutionary that residents were split on the issue.

“To most people, lowering the voting age is a second look issue,” FairVote’s Director Rob Richie said. “While the knee-jerk reaction is to reject to idea, all evidence suggests that cities will increase turnout by allowing citizens to cast their first vote after turning 16.” A detailed study on voting age supports this claim. In Denmark, research showed that 18-year-olds were far more likely to cast their first vote than 19-year-olds, and that every month of extra age made voters less likely to turn out for their first election. People who start voting early tend to keep voting throughout their lifetimes. As a result, casting a first vote at 16 increases the likelihood of becoming a lifelong voter.

The Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE) of Tufts’ University also supported the proposal. CIRCLE’s Director Peter Levine wrote the mayor and city council a letter endorsing the proposed change. Levine asserted that “16 and 17-year-olds are not too young to vote.” He cited a study finding that 16 and 17-year-olds’ political knowledge is about the same as 21-year-olds’, and quite close to the average knowledge of all adults.

Perhaps the most influential advocates of this policy were the youth of Takoma Park. Many attended the council meetings and testified on local issues about which they were passionate. Other young people produced videos describing how they had been involved in their community and what it would mean to them to have the right to vote. Some signed petitions and rallied support among their friends and families. Their civic engagement and commitment to advancing the change helped sway public opinion in favor of lowering the voting age.

The Beginning of a Movement

In May, the proposal passed with a 6-1 vote. By November, 16- and 17-year-olds were voting alongside adults in Takoma Park elections.

While Takoma Park has become the first city to extend voting rights to residents after they turn 16, it’s unlikely to be the last. Following the decision to lower the voting age in Takoma Park, CIRCLE convened a commission of experts on youth voting and civic knowledge to release a report on innovations for youth engagement. Lowering the voting age in municipal and state elections was among the group’s recommendations for improving youth voter participation. As election and youth experts endorse a lower voting age, we’ll likely to see more cities expanding suffrage to young people.

The seeds of this change were planted last winter, when Councilmember Tim Male began crafting a Right to Vote Resolution -- in partnership with FairVote’s Promote Our Vote project. The resolution called for a constitutional right to vote, established a voting task force, and took stances on a variety of voting rights issues. By sparking city-wide dialogue about what it means to vote and be civically engaged, the resolution catalyzed efforts to lower the voting age. As Male explained to FairVote, the Right to Vote Resolution created an environment where the idea of a lower voting age – one that several of his colleagues initially treated with skepticism – was taken seriously.

By spring, the city was engaged in a lengthy debate over the charter amendment that, among other changes, lowered the voting age in city elections. Central to this discussion was the city’s youth turnout crisis. A mere 14 voters between the ages of 18 and 25 showed up to cast a ballot in Takoma Park’s last contested mayoral race. That dismal number means that more than 99% of Takoma Park residents between the ages of 18 and 25 did not vote. While the city agreed that it had to improve youth turnout, lowering the voting age seemed so revolutionary that residents were split on the issue.

“To most people, lowering the voting age is a second look issue,” FairVote’s Director Rob Richie said. “While the knee-jerk reaction is to reject to idea, all evidence suggests that cities will increase turnout by allowing citizens to cast their first vote after turning 16.” A detailed study on voting age supports this claim. In Denmark, research showed that 18-year-olds were far more likely to cast their first vote than 19-year-olds, and that every month of extra age made voters less likely to turn out for their first election. People who start voting early tend to keep voting throughout their lifetimes. As a result, casting a first vote at 16 increases the likelihood of becoming a lifelong voter.

The Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE) of Tufts’ University also supported the proposal. CIRCLE’s Director Peter Levine wrote the mayor and city council a letter endorsing the proposed change. Levine asserted that “16 and 17-year-olds are not too young to vote.” He cited a study finding that 16 and 17-year-olds’ political knowledge is about the same as 21-year-olds’, and quite close to the average knowledge of all adults.

Perhaps the most influential advocates of this policy were the youth of Takoma Park. Many attended the council meetings and testified on local issues about which they were passionate. Other young people produced videos describing how they had been involved in their community and what it would mean to them to have the right to vote. Some signed petitions and rallied support among their friends and families. Their civic engagement and commitment to advancing the change helped sway public opinion in favor of lowering the voting age.

The Beginning of a Movement

In May, the proposal passed with a 6-1 vote. By November, 16- and 17-year-olds were voting alongside adults in Takoma Park elections.

While Takoma Park has become the first city to extend voting rights to residents after they turn 16, it’s unlikely to be the last. Following the decision to lower the voting age in Takoma Park, CIRCLE convened a commission of experts on youth voting and civic knowledge to release a report on innovations for youth engagement. Lowering the voting age in municipal and state elections was among the group’s recommendations for improving youth voter participation. As election and youth experts endorse a lower voting age, we’ll likely to see more cities expanding suffrage to young people.